Eastern Sierra Nevada, California and Nevada

Eastern Sierra Nevada, California and Nevada

Tom Schweich

Eastern Sierra Nevada, California and Nevada

Eastern Sierra Nevada, California and Nevada

| A Checklist Flora of the Mono Lake Basin, Mono County, California and Mineral County, Nevada. |

|

Tom Schweich |

Topics in this Article: Floristic Tour of the Mono Basin Plant Collectors in the Mono Basin Checklist of the Mono Basin Flora Checklist of the Upper Mono Basin Flora Literature Cited |

(For the botanical season of 2016, I plan to make one field trip to the Mono Lake basin, the timing of which depends on how this promising El Nino season develops. I made one field trip to Mono Lake in 2015, collecting at Warm Springs, and the south side of Grant Lake, among other places. All of my collections from the Mono Lake basin have been determined and distributed to herbaria, with the exception of some willows. There are always collections of mine to identify and collections of others to review, especially while California herbaria continue to come online at the Consortium of California Herbaria. As always, comments and suggestions will be cheerfully received. Tom Schweich, February, 2016.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

|

No matter how you first see it, Mono Lake will always impress. The view from Conway Summit, the descent from Tioga Pass, the bitter alkaline water, or the strange and fantastic tufa towers never fail to leave an indelible impression. Nestled into a tectonic depression, but still at a high altitude (higher than Lake Tahoe), at the boundary between the high Sierra Nevada and the Great Basin, significant botanic shifts should be visible across short horizontal distances. Things are always more exciting at the interfaces, whether we're talking about geology, botany, food or music. There's no reason why the Mono Lake basin should be any different. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I adopted this project because it seemed that such a place needed an updated list of plants that make the basin their home. I hope that you enjoy learning about the plants of the Mono Lake basin, and that the checklist makes a valuable addition to your visit. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I have tried to make this flora strongly collections-based, i.e., there is at least one publicly accessible collection for every taxon listed. The Internet and online herbaria data bases, especially the Consortium of California Herbaria (ucjeps.berkeley.edu/consortium/) made this possible. I am very indebted to the University and Jepson Herbaria for making the California data available for examination in the middle of the night … while wearing my robe and pajamas, … and my bunny slippers. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

|

Nomenclature is intended to follow The Jepson Manual, 2nd Edition (2012), to the extent that I can keep track of it. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Definition of the Mono Lake Basin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Location of Mono Lake in the Southwest Location of Mono Lake in the Southwest

|

The Mono Lake basin is a closed, internal-drainage basin located east of Yosemite National Park in California, United States.

It is also directly east of the San Francisco Bay Area, 180 miles as the California gull (Larus californicus) flies, and 232 miles by road over Tioga Pass.

It is bordered to the West by the Sierra Nevada, to the East by the Cowtrack Mountain, to the North by the Bodie Hills, and to the South by the North ridge of the Long Valley.

The current lake surface is at an elevation of 6378 feet, higher than Lake Tahoe (elev. 6224 ft.). The waters are alkaline (pH: ˜ 10), because they contain carbonates and sulfates in addition to chlorides. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

Geologically, Bursik and Sieh (1989) describe the Mono Lake basin as the area bounded by the Bodie Hills, Cowtrack Mountain, Long Valley Caldera, and the Sierra Nevada on the north, east, south, and west. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

From a structural geology perspective, the Mono Lake basin is a down-warped structural basin bounded by flexures on the north, east, and west, and bounded by the Sierra Nevada frontal fault on the west. Structural development of the basin has occurred largely in the last 3 m. y. and is still in progress (Gilbert, C. M., M. N. Christensen, Yehya Al-Rawi, and K. R. Lajoie. 1968).

This area of California was a passive continental margin during the Paleozoic. During the Mesozoic through about Miocene it was an active continental margin, perhaps somewhat like the west coast of South America at present. Before the Sierra orogeny (~ 3.2 ma.), it drained west through the San Joaquin River canyon. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| From a hydrographic perspective, the Mono Lake basin is defined by all streams that drain into Mono Lake. On the north, east and south, the hydrographic basin coincides roughly with the structural basin. However, on the west, the Mono Lake basin extends west of the Sierra Nevada frontal fault to the Sierra crest. Thus Tioga Pass, Mount Dana and Mount Conness are all on the western boundary of the Mono Lake basin. Major streams in the Mono Lake basin that originate in the high Sierra are Rush Creek, with tributaries Parker Creek and Walker Creek, Lee Vining Creek, and Mill Creek. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

From a biogeographical perspective, I have found no definition of Mono Lake basin. The Jepson Manual (Hickman, 1993), places the lower portions of the Mono Lake basin in East of Sierra Nevada (SNE) which includes the Sweetwater Mountains, Bridgeport Valley, Bodie, Mono Lake basin, Long Valley, and the Owens Valley. The CalFlora Ecological Sub-Units divide the basin into Northern Mono (MNOn) and Southern Mono (MNOs). These sub-units extend to the Sierra crest on the west. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overview Map of Mono Lake basin Overview Map of Mono Lake basin

|

My definition of the "Mono Lake basin" includes the entire hydrographic basin, less that portion on the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada above 8400 ft. (2560 m).

The separation of Upper Mono Lake basin from Mono Lake basin at 8400 feet is based upon several geographic objectives:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

Some include Alkali Valley in the Mono Lake basin, and some not. Russell (1889, 300-301) did not believe the waters of Pleistocene Lake Mono entered the present day northern part of Alkali Valley. He based his conclusion on the absence of wave cut terraces around the valley. However, Reheis, et al. (2002) show that a paleovalley, now beneath an andesite flow from Mount Hicks, could have been a spillway. This evidence is supported by presence of well rounded, polished pebbles and cobbles in a terrace below Hicks Valley. I include the northern part of Alkali Valley in my definition of the Mono Lake basin because it appears that it was filled by the waters of Pleistocene Lake Mono. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Mono Basin.

|

Floristic Research in Nearby Areas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

Locations: Sweetwater Mountains. |

The Sweetwater Mountains are 20 km north of the Mono Lake basin. There are two published papers and an informal checklist of plants found there. Lavin (1983) published a paper on the floristics of the Upper Walker River, California and Nevada. Among other findings was a 90 percent floristic similarity (Sorenson's) between the Sweetwater Mountains, lying to the east of the Sierra, and the east slope of the Sierra Nevada (within the Walker River drainage), which indicates the Sweetwaters to be more affiliated with the Sierran flora instead of the Intermountain flora. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

Locations: Sweetwater Mountains. |

Hunter and Johnson (1983) concentrated on the alpine flora of the Sweetwater Mountains, also finding a closer affinity between the Sweetwater Mountains and the eastern Sierra Nevada than with the Great Basin mountain ranges. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Marty Wojciechowski (Arizona State University) prepared a checklist for a Flora of the Sweetwater Mountains Workshop sponsored by the Jepson Herbarium, University of California, Berkeley, in June 2002. I haven't seen this checklist. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

Locations: Bodie Hills. |

Tim Messick wrote a flora of the Bodie Hills as his Masters thesis in 1982 at Humboldt State University. Messick's results were also aggregated into Lavin (1983) above. An abbreviated version of Messick's thesis, without references to voucher specimen numbers and individual specimen locations, is available at his web site (http://www.timmessick.com). Messick deposited 1,170 vouchers at the herbarium of Humboldt State University (HSU). While HSU is a member of the Consortium of California Herbaria, their specimen data base is not fully available online at this time (October, 2009). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

Ann Howald (1989) prepared a vegetation and flora of the Mammoth Mountain Area and followed that in 2000 with a flora of Valentine Eastern Sierra Reserve. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

Locations: Glass Mountain. |

To the south of the Mono Lake basin, Michael Honer's vascular flora of the Glass Mountain region (Honer, 2001) covers a region just to the southeast of the Mono Lake basin. There is some overlap between in the areas covered by this flora and the Glass Mountain flora. In particular, the areas of Big Sand Flat and Little Sand Flat are covered by both. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

Locations: White Mountains. |

Lloyd and Mitchell's (1973) Flora of the White Mountains, California and Nevada, was the first published flora of the White Mountains. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

The most recent floristic checklist of the White Mountains is Morefield, Taylor, and DeDecker (1988). The number of taxa on their checklist represented a 41.7% increase over the Lloyd and Mitchell flora of 15 years previous. At the end of field work in 1987, taxa new to the White Mountains were being discovered at a constant rate of about two every three days of work in previously unexplored areas. The authors note that the list remains far from complete and that field work continues. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

Mary DeDecker contributed Chapter 6 - Shrubs and Flowering Plants in Hall's (1991) Natural History of the White-Inyo Range. A chapter on trees was contributed by Deborah L. Elliot-Fisk and Ann M. Peterson. Timothy Spria's chapter on Plant Zones is based on Mooney's treatment in Lloyd and Mitchell (1973). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

The northern Mojave Desert, comprised of the Eureka Valley, Saline Valley, Death Valley, and Panamint Valley, and their surrounding mountains, south to the approximate border of San Bernardino County was covered by Mary DeDecker's (1984) Flora of the Northern Mojave Desert. The Mono Lake basin is separated from that area by about 50 miles including the bulk of the White Mountains. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

Simpson and Hasenstab's (2009) Cryptantha of Southern California explicitly excludes the Mono Lake basin. However, a comparison of taxa included in their paper shows that only C. ambigua is missing from the list of taxa, while 13 of the 56 taxa listed are found in the Mono Lake basin. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Publications about Plants in the Mono Basin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

The original work by the Mono Basin Research Group has been reported in Winkler (1977). The plant collections were mainly by J. Burch, J. Robins, and T. Wainwright, and they deposited about 200 vouchers from around the lake at DS (Dudley Herbarium, Stanford University), which is now at CAS (California Academy of Sciences). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

Helen Constantine's (1993) Plant Communities of the Mono Basin published by the Mono Lake Committee is a nice introduction to local plant communities. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

In the past, I have carried the Jepson Desert Manual with me in the field. The Mono Lake basin is included within the East of Sierra Nevada (SNE) region, and the illustrations in the Jepson Desert Manual are helpful. However, with the publication of the 2nd edition of the Jepson Manual and its many name changes, I don't find the Jepson Desert Manual as useful in the Mono Lake basin as other regional floras. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

Sometimes it's helpful to just have a book of photographs of common plants. For the Eastern Sierra, that would be Blackwell's Wildflowers of the Eastern Sierra. I usually take this book in my portable library, though not in my day pack. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

Most of the vegetation types in the Mono Lake basin can be described Sawyer, et al.'s (2008) 2nd edition of the Manual of California Vegetation, except two possible unique types found in the Mono Dunes and the large sand flats south of the lake. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

One of the books I carry in the field is Dean Taylor's Flora of the Yosemite Sierra. This flora explicitly includes the Mono Lake basin. I very much appreciate the somewhat different take that Taylor has on the flora of the region and some of the features he has included in his book, such as a less-rigid structure in his keys, helpful notes and comments, specific vouchers examined, and occasional gems of humor.

Taylor also produced three lists in the early 1980s, one each for the H. M. Hall RNA (Research Natural Area), one for Indiana Summit RNA, and a third for Mono Lake. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

Indispensible because of all the recent revisions to current nomenclature, The Jepson Manual, 2nd edition, is a necessary reference for the Mono Lake basin. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Floristic Tour of the Mono Basin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Let's take a geographical tour of the Mono Lake basin, starting at the Mono Lake Committee and proceeding in a clockwise direction. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

Other articles:

Locations: Lee Vining. |

Mono Lake Committee

David Winkler chose to pursue a doctorate degree, which left David Gaines and Sally in charge of the Committee. David and Sally traveled around the state showing a slide show on Mono Lake to schools, conservation groups, legislators, and anyone who would listen. They decided on a three-part plan of action: legal, legislative, and educational. They also decided to ask for exactly what they wanted, instead of asking for more and then compromising down to the true goal. In 1979, a Lee Vining storefront was acquired for an office. The Mono Lake Committee Information Center & Bookstore opened at this location on Memorial Day weekend in 1979. In order to attract more visitors, the Information Center also functioned as the Lee Vining Chamber of Commerce. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

|

Mono Basin National Forest Scenic Area Visitor CenterThe Mono Basin National Forest Scenic Area Visitor Center provides regional information to travelers visiting the Mono Basin Scenic Area in the Eastern Sierra and Yosemite National Park. View exhibits on Mono Lake history, wildlife, geology, and access the interpretive trail. Docent led tours of Mono Lake, South Tufa, or Panum Crater are available.The Eastern Sierra Interpretive Association (ESIA) operates the bookstore at the visitor center, with a comprehensive selection of books and maps of the region. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Old Marina.

|

Old MarinaThe Old Marina is on the shore of Mono Lake, just north of Lee Vining Creek. You can take Mattley Avenue from near the Forest Service Information Center, or by taking US Hwy 395 north to Picnic Grounds Road.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

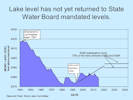

Lake levels not returned to state-mandated levels Lake levels not returned to state-mandated levels

|

The surface of Mono Lake stood at 6417 feet when diversions of Mono Lake basin waters to Los Angeles began. The lake reached its nadir in December 1979 and January 1980 with a lake level of 6373 feet, 43 feet lower.

A series of lawsuits, legal actions, and administrative hearings, begun in 1979 and continuing to day, resulted in State Water Board Decision 1631, which set a target lake level for Mono Lake of 6392 feet, established minimum flows and annual peak flows for the creeks, and ordered DWP to develop restoration plans for the streams and for waterfowl habitat. As shown in the chart prepared by the Mono Lake Committee, lake level has not yet returned to State Water Board mandated level of 6392 feet. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Picnic Grounds.

|

Picnic GroundsThis is the best turnoff for the road to Old Marina, for Picnic Grounds access, and the David Gaines Memorial Boardwalk.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Andy Thompson Creek.

Tioga Lodge.

|

Tioga LodgeWhat we now call the Tioga Lodge was first Hammond Station, and then the Mono Lake Post Office, before becoming Tioga Lodge.

The delta of Andy Thompson Creek, below Tioga Lodge, is a place all three species of orchid found in the Mono Lake basin can be found growing together. The orchids are Epipactus gigantea Hook. Stream Orchid, Platanthera dilatata (Pursh) Lindl. ex Beck var. leucostachys (Lindl.) Luer. Sierra Bog Orchid, and Platanthera sparsiflora (S. Watson) Schltr. Sparse-Flowered Bog Orchid. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Mono Lake, northwest shore (as a col. locality).

|

Northwest Shore of Mono LakeThe northwest shore of Mono Lake is probably the most densely collected area in the Mono Lake basin. Primary collectors here are Carl W. Sharsmith, who made a third (34) of his Mono Lake collections here. The California Geological Survey accounts for 32 collections here, in their two visits led by Wm. H. Brewer, July 9-11, 1863, and Henry N. Bolander in 1866. Dean Wm. Taylor made 29 collections at the northwest shore. And, Malcolm A. Nobs and S. Galen Smith made 23 collections in wetlands along the northwest shore in their single pass from north to south through the basin. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Dechambeau Creek.

Thompson Ranch.

|

Dechambeau Creek and Thompson Ranch

Along one of these ditches I found Hypericum scouleri and Myosotis laxa. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Mono Lake County Park.

|

Mono Lake County ParkGreat place for a picnic, the Annual Chautauqua picnic is held here, and a stroll down the boardwalk to the lake.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Mill Creek.

|

How did the Bay-Forget-Me-Not get to the Mono Lake basin? Since it is found in Mill Creek below Mono City, my guess it that it is a garden escapee. The seed is available commercially, and no special preparation is required. The plants are easy to grow, as long as they have some water. Where is it found now? Myosotis laxa is found along Mill Creek from US Highway 395 past Mono City all the way to its delta and Mono Lake. It can be seen from the boardwalk at Mono Lake County Park, and in wet areas of the former Thompson Ranch above the county park. Continuing around the northwest shore of Mono Lake, Myosotis laxa can be found in the delta of Andy Thompson Creek, along the boardwalk at Picnic Grounds, and in the delta of Lee Vining Creek. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Lundy Canyon.

Lundy Lake.

|

Lundy CanyonLundy Canyon is the northernmost canyon emptying into the Mono Lake basin. As with the other western canyons, the floor of Lundy Canyon, including Lundy and Lundy Lake, are in the (lower) Mono Lake basin, and most every location above there is in the Upper Mono Lake basin. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

Other articles:

|

Miss Maud MinthornThere are 75 vouchers of collections made by Miss Maud Minthorn in the vicinity of Lundy during the summer of 1908. Maud Aileen Minthorn (26 March 1883-1966), was born in Plymouth County, Iowa to Pennington Wesley Minthorn and Anna Mary Heald. Her brother was Theodore Wilson Minthorn, who made a few plant collections himself. After graduating from the State Normal School in Los Angeles in 1904, Miss Minthorn taught school in Lundy. All of her collections from Lundy are dated from the summer of 1908. This would imply that Miss Minthorn was in Lundy for a single school year. All of Miss Minthorn's Mono Lake basin collections give "vicinity of Lundy" as the collection location. I have assigned all of the collections to the lower portion of the Mono Lake basin. It is likely, however, that some of the collections were made above 8400 feet and, therefore, would have been assigned to the upper Mono Lake basin were more detailed location information available. There is one plant named for Miss Minthorn: Astragalus minthorniae (Rydb.) Jepson. (Fl. Calif ii. 374, 1936, Syn: Hamosa minthorniae Rydb. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 54:15, 1927). The type locality is Pioche, Lincoln County, Nevada. This was Miss Maud Minthorn's collection number 77 made on 24 April 1909. The holotype is at NY (Herbarium of the New York Botanical Garden). Miss Minthorn also collected Frasera albomarginata in the vicinity of Pioche, Nevada Nevada, on 9 June, 1909, her collection #44. Miss Minthorn received an undergraduate scholarship from the State of California for the school year 1910-1911 and wrote an M. S. thesis titled "The nine-point conic," at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1912. After earning her masters she taught high school math in Fresno, California for many years. After retiring she lived in the San Fernando Valley, but died in Pinellas Park, Florida, in 1966.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Bodie Hills.

Copper Mountain.

Mono Diggins.

|

The western boundary of the Mono Lake basin in Lundy Canyon becomes the northern boundary by snaking out of Lundy Canyon and across the face of Copper Mountain to Conway Summit, elevation 8143 ft. (2482 m.). Between Copper Mountain and Conway Summit is the headwaters of Wilson Creek, most of which is below the 8400 foot boundary between the lower and upper basin. Copper Mountain is named for the small copper deposits in the only massive limestone of the Mono Lake basin. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The northern boundary of the Mono Lake basin comprises portions of the Bodie Hills from Conway Summit, to the Mount Hicks Spillway in Mineral County, Nevada. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Conway Summit.

|

Conway SummitFrom Conway Summit the northern boundary passes north of Rattlesnake Gulch and Rancheria Gulch to an unnamed hill at elevation 8662 feet. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Rattlesnake Gulch.

|

Rattlesnake GulchRattlesnake Gulch in Mono Diggin’s is a great location name for a collection. Cord Norst is credited with discovering gold here on July 7, 1859. While I've done a little collecting here, so far I haven't found anything unusual, except perhaps a specimen I identified as Potentilla gracilis var. fastigiata, which is not typically found away from the higher mountain ranges. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

|

Along Goat Ranch Cutoff, windblown sand from the Mono Dunes and volcanic detritus at the foot of the Bodie Hills mix to form a little different soil. Here, I have collected Oenothera cespitosa Nutt. Ssp. marginata (Hook. & Arn.) Munz, Tufted Evening Primrose, and Camissonia parvula (Torr. & A. Gray) P. H. Raven, the Lewis River Suncup, growing right next to each other. I also collected four different species of Cryptantha growing within a few meters of each other. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

|

A little more than four miles west of US Highway 395 along California Highway 167 is a good place to see the stabilized sand dunes below former shoreline of Pleistocene Lake Mono. This is the type locality and prime habitat of Tetradymia tetrameres (S. F. Blake) Strother. All collections of this taxon have been in this area except one, collected in Adobe Valley by Mary DeDecker.

This is also the location of the few collections of Atriplex canescens (Pursh.) Nutt. Var. canescens, Four-wing Saltbush, in the Mono Lake basin. Why it is found only here, I don't know; perhaps some seed fell off a truck carrying hay, sheep, or cattle. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Dechambeau Ranch and PondsThe hot spring feeding Dechambeau Ponds has attracted some botanical attention. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

Other articles:

Locations: Black Point. |

Black PointBlack Point was a volcano that erupted under the waters Pleistocene Lake Mono. The shape of Black Point was subsequently modified by erosion. One interesting feature of Black Point is the Fissure, a crack in the top of Black Point big enough to walk into.

Gilbert et al. (1968) suggested that the volcanoes of Mono Lake are related to the “structural knee” of the western Great Basin, a region in which bedrock structures rotate from north-northwest trends to northeast trends as they are followed from south to north. They concluded that Black Point and the volcanoes of Mono Lake are localized at the apex of the knee, where there should be almost pure extension, as exhibited by the Black Point fissures. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Bridgeport Canyon.

|

Bridgeport CanyonThe northern boundary crosses an unnamed pass at the head of Bridgeport Canyon, then crosses several peaks to a small peak (8717 ft) 2/3 mile west of Mount Biedeman. Looking just ahead on the road it, dips where it is crossed by a small watercourse. There is also a small watercourse parallel to the road on the left (east). Within this “point bar” where the two watercourses merge is a south-facing natural area that has the look of someone's carefully tended rock garden. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Bridgeport Canyon.

|

In the dry year of 2013, this interesting natural rock garden was in full bloom. The Lewisia made me stop and investigate. But what I found kept me there for three hours. Twelve species of plants were collected, all in bloom.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

|

Before my collection of the Mountain Tarweed (Madia glomerata Hook.) near Reversed Creek, there was a single collection of another Madia in the Bodie Hills. Tim Messick collected the Grassy Tarweed (Madia gracilis (Sm.) D. D. Keck & J. C. Clausen ex Applegate) in a roadside ditch such as that shown in the photograph. I have since tried to repeat that collection. However, my own #894 from approximately the same location has turned out to be M. glomerata, the Mountain Madia. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Locations: Mount Biedeman. |

Mount BiedemanFrom the small peak west of Mount Biedeman, then northern boundary turns north to a small pass and California Highway 270 in the Cottonwood Canyon drainage. Mount Biedeman itself is entirely inside the Mono Lake basin, as the north side drains into the basin through Cottonwood Canyon, while the south side drains into Bridgeport Canyon and the Goat Ranch area. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Sulphur Pond.

|

Sulphur PondAmong the sand dunes between the lake and California Highway 167 is Sulphur Pond. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Bodie & Benton RailwayThe Bodie & Benton Railway was a 3 ft narrow gauge common carrier railroad in California, from the Mono Mills to a terminus in Bodie, now a ghost town, in Mono County. It was unusual among U.S. railroads in that it was completely isolated from the rest of the railroad system. As the Bodie Railway & Lumber Company, the railroad was established in 1881 to link the gold-mining town of Bodie to the Bodie Wood and Lumber Company's newly built sawmill, Mono Mills, 32 miles south of Bodie along the eastern shore of Mono Lake. The line was completed and operational on November 14, 1881. Temporary spurs into timberlands were built in 1882. When the railway ceased to be profitable in 1918, due primarily to a decline in mining activity in Bodie, the rails and all valuable equipment were pulled up and sold. The rails and equipment were trucked from the southern terminus at Mono Mills along what is today State Route 120, to the rail line at Benton for transport south. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

Other articles:

Locations: Black Point. South Tufa Area. Warm Springs. |

Warm SpringsOn the far eastern shore of Mono Lake is Warm Springs. Here a number of small warm (85°F.) springs create a fairly broad area of wetlands.

The type was collected by Dr. Torrey in 1865 and described by Asa Gray in 1874. Torrey's label on the isotype (NY112230) states the collection was made on the “sterile saline plains of Humboldt County, Nevada.” I assume this would be somewhere northwest of Winnemucca. However, a hand-written note on another voucher (NY112231) suggests the collection was made “in a valley west of Job's (sic) Peak, Nevada.” The valley west of Job Peak, Nevada, would be the Lahontan Valley containing the Carson Sink near Fallon, Churchill County, Nevada. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Cottonwood Canyon.

Murphy Spring.

|

Cottonwood CanyonEast and north of Mount Biedeman, the Cottonwood Canyon drainage extends deeply into the Bodie Hills, about 5 miles north of California Highway 270, all the way to the summit of Bodie Hill. For the purposes of this checklist, I exclude the portions of the Cottonwood Canyon drainage north of California Highway 270.

California Highway 270 exits the Mono Lake basin at a small pass at about 1.5 miles southwest of Bodie. The basin boundary swings south and then east across an unnamed hill to a pass just north of Sugarloaf. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

SugarloafThe hill known as Sugarloaf, south of Bodie and California Highway 270, is good landmark for eastern edge of the Cottonwood Canyon drainage. Sugarloaf itself is entirely inside the strict definition of the Mono Lake basin, as all of its slopes drain into Cottonwood Canyon. Just a half mile north of Sugarloaf is a small pass through which Cottonwood Canyon Road enters the Bodie Creek basin from Cottonwood Canyon. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The road to Bodie from the Mono Lake basin passes through Cottonwood Canyon. It is the largest single canyon in the Bodie Hills that drains into the Mono Lake basin. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Bodie.

|

BodieThe mining town is Bodie is just north of the Mono Lake basin. Bodie Creek drains north, ultimately into the East Walker River and then to Walker Lake. Bodie began as a mining camp of little note following the discovery of gold in 1859 by a group of prospectors, including W. S. Bodey. Bodey perished in a blizzard the following November while making a supply trip to Monoville (near present-day Mono City, California), never getting to see the rise of the town that was named after him. The district's name was changed from "Bodey," "Body," and a few other phonetic variations, to "Bodie," after a painter in the nearby boomtown of Aurora, lettered a sign "Bodie Stables." Gold discovered at Bodie coincided with the discovery of silver at nearby Aurora (thought to be in California, later found to be Nevada), and the distant Comstock Lode beneath Virginia City, Nevada. But while these two towns boomed, interest in Bodie remained lackluster. By 1868 only two companies had built stamp mills at Bodie, and both had failed. Two of the more interesting people who visited Bodie and Aurora were: Israel Russel and Mark Twain. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

Israel C. RussellOf the many prople associated with Bodie, one of the more productive was Israel C. Russell.Born at Garrattsville, New York, in 1852, he received B.S. and C.E. degrees in 1872 from the University of the City of New York (now New York University), and later studied at the School of Mines, Columbia College, where he was assistant professor of geology from 1875-77. In 1878 he became assistant geologist on the United States geological and geographical survey west of the 100th meridian, becoming a member of the United States Geological Survey in 1880. Between 1881 and 1885 he worked at Mono Lake in east-central California. Originally employed for work with regard to surveying and building the Bodie Railway connecting Bodie to Mono Mills, he stayed for four years and wrote the seminal work Quaternary History of Mono Valley, California (1884). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

Locations: Mono Lake. |

Mark TwainMark Twain (Samuel Clemens), one of America's best-known writers, began his literary career after several of his letters to the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise were published in the summer of 1862. He wrote those letters while living with his mining partners at Aurora, Nevada. Twains's residence in Aurora was relatively brief, beginning in the spring of 1862, so that he could personally attend to the many mining claims he and his brother had purchased. His first job at Aurora was as a miner digging and blasting tunnels in some of their more promising claims. Unfortunately, neither his labor as a miner, nor his speculation in Aurora’s mines, provided any income. Since his only paying job “as a common laborer in a quartz mill, at ten dollars a week and board,” lasted only a week, Sam was forced to live off money sent to him by his brother in Carson City. Twain never thought much of Aurora. He was eager to leave there during the fall of 1862 for his new job as a reporter in Virginia City. In his last letter from Aurora he complained, “ I don't think much of the camp -- not as much as I did.” He certainly didn't like living in his “wretched” cabin. He never returned. It wasn't until the 1872 publication of Twain's semi-autobiographical book “Roughing It” that he would write of his visit to Mono Lake.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Brawley PeaksFrom Sugarloaf just south of Bodie, the northern boundary curves north to the Brawley Peaks before turning east between Aurora Peak and Spring Peak. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Alkali Valley.

|

Spring Peak | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Locations:

Mount Hicks.

Mount Hicks Spillway.

|

Mount Hicks and Mount Hicks SpillwayThe Mono Lake basin boundary goes northwest to Mount Hicks and then curves northeast to the Mount Hicks Spillway, the most northern point of the basin at the north end of Alkali Valley. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

Locations: Alkali Valley. |

Alkali Valley

The name of Lake Russell for the Pleistocene lake was proposed by W. C. Putnam (1949). Russell himself proposed to use Lake Mono for the Pleistocene lake filling the basin occupied by the current Mono Lake. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

|

Hesperochiron californicus (Benth.) Watson, with a unusual common name of California Monkey-fiddle, is fairly common in the west, being found throughout mountainous eastern California in Yellow Pine Forest, Red Fir Forest, Lodgepole Forest, and wet meadows, flats, valleys, to Oregon, Washington, Montana, Wyoming, Utah, and Baja California.

There are five collections in Long Valley, and two in Bridgeport Valley, but none from the Mono Lake basin, except for my collection in Alkali Valley. Given the location that it was found, on the muddy edge of an alkali playa, at the edge of the sagebrush, it seems surprising that it has such a wide distribution of geography and habitat. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Adobe Hills Spillway.

Anchorite Pass.

|

Anchorite HillsFrom the Mount Hicks spillway, the northern boundary passes across Powell Mountain and then curves south across Table Mountain and through the Anchorite Hills to the main eastern landmark at Anchorite Pass on Nevada Highway 359 (California Highway 167 on the California side of the state boundary).The eastern boundary of the Mono Lake basin from Anchorite Pass to the Adobe Hills Spillway is pretty vague through the Adobe Hills as there are few well-known landmarks. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

Other articles:

|

The extreme dryness has greatly limited the understory vegetation, perhaps creating a fire-safe location for these very large Junipers near the Nevada border (Barbour, et al., 2007). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

Other articles:

Locations: Basalt. Hereford Valley Ranch. Project Flambeau, Experimental Fire 460-14-65. Project Flambeau, Experimental Fire 460-7-66. |

Deep Cañon

In a good wet year, this area could use some botanical attention. There is also some sort of odd patterned ground out here. At the surface it's a little difficult to recognize, but, on GoogleEarth, it's obvious that someone was out here tearing up the landscape. Having looked at it on the ground, I doubt it was the result of Pinyon clearance. The pattern is rectilinear, and there are a few anchor eyes visible above the surface. It looks more like an antenna experiment, in which cables were buried in a rectilinear pattern to provide a ground plane below an antenna or a tower. An article in the April 3, 2017, issue of High Country News provided the necessary clue to the source of this odd patterned ground when the author (Fox, 2017) referred to large fires set east of Mono Lake in “Project Flambeau.” In 1962, the Forest Service in cooperation with the Department of Defense undertook a large-scale investigation – called Project Flambeau – to add to current knowledge of the characteristics and behavior of mass fire. The study was not designed to develop cause-and-effect relationships, but rather to gain some insight into as many aspects as possible of mass fire. A series of test fires were burned on isolated sites in California and Nevada. Five of the fires were conducted near Basalt, Mineral County, Nevada. Two fires were on the east side of Mono Lake, near Deep Cañon. And two more fires were near Queens Valley Ranch, Mineral County, Nevada (Palmer, 1969). The ranch in the section given by Palmer, T1N R33E S18, is called the Hereford Valley Ranch on USGS maps and in the GNIS. The data collected were intended to provide information about large free-burning fires for use in development of realistic theoretical and experimental studies aimed at solving specific mass fire problems. The investigation was focused on urban fires and civil defense problems, but information obtained should be useful for other purposes as well (Countryman, 1969). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Adobe Hills Spillway.

|

Adobe Hills Spillway

At the spillway is a fresh water sandstone with fossil snail shells. There are a few Ipomopsis congesta (Hook.) V. E. Grant ssp. congesta (Ballhead Ipomopsis) growing on the sandstone. Most other collections of Ipomopsis congesta, typically in the high passes on the west side of the Mono Lake basin, are of ssp. montana. In fact, with the exception of two collections in the Inyo Mountains, most collections of ssp. congesta were made far to the north in Lassen, Shasta, and Siskiyou counties. Determination of subspecies of Ipomopsis congesta is made by the lobing of leaves, which is pinnate for ssp. congesta and palmate for montana. The leaves of the collections made at the Adobe Hills Spillway are clearly pinnate, leading to a determination of ssp. congesta. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Cowtrack Mountain.

Sagehen Summit.

|

Cowtrack Mountain

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

|

Between Cowtrack Mountain and Sagehen Summit, the boundary of the Mono Lake Basin passes through a relatively narrow (1/2 mile) and long (3 miles) unnamed valley. To the south this valley drains through North Creek into Adobe Valley. To the north, it drains through Indian Spring to Mono Lake. North northwest trending faults are drawn through this valley, extending all the way to Warm Spring on the shore of the lake. To the south southeast, several faults are drawn, extending approximately to Sentinal and Wet Meadows on the north face of Glass Mountain. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Indian Spring.

|

Indian Spring is likely a perennial source of water. Unfortunately, it is deeply incised, probably due to heavy use by grazing animals. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Big Sand Flat.

|

Sagehen Summit

Big Sand Flat is a half mile wide by 3½ miles long. It was formed by faulting on the northwest side. Big Sand Flat is also the type locality of Lupinus duranii Eastw., the Mono Lake Lupine (Victor Duran, #3343, July 15, 1932, vouchers at CAS, DS, GH, NY, POM, RSA, UC, UCD). In wet years, it often puts on a good show with Mimulus nanus Hook. & Arn. Var. mephiticus (Greene) D. M. Thomps., the Mono Lake form of the Skunky Monkey Flower. While not the type locality of Astragalus monoensis Barneby, the Mono Milk-Vetch, the taxon can be found scattered around the flat. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dry Creek enters Big Sand Flat at the eastern end of the flat. There is perennial water here, enough to maintain a very small wetland. The spring has been enlarged or dug out, presumably to permit pumping of water for sheep grazing. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Dry Creek.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

|

Found sparingly around Big Sand Flat and the upper reaches of Dry Creek is Penstemon cinicola D. D. Keck, the Ash Penstemon.

It is somewhat reminiscent of Penstemon rydbergii A. Nelson var. oreocharis (Greene) N. H. Holmgren, which is found on the west side of the Mono Lake basin, but obviously different when seen side-by-side.

The type of P. cinicola is a collection of Keck, D. D., and Jens Clausen, #3690, made June 23, 1935, just north of Lapine, Deschutes County, Oregon. The best displays of the Ash Penstemon are at Crooked Meadows, just outside the Mono Lake basin. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Mono MillsJeffrey pine forests around Mono Mills were logged to supply Bodie, 1877-1932. Gold was discovered there in 1859 by a group of prospectors, including W. S. Bodey. The Bodie Railway & Lumber Company (1881) was formed to supply the mines with timber and cord wood. Maps generally show that the railroad came as far south as the mill and then stopped. However, there is adundant evidence, in the form of graded roadbed and rotted railroad ties, to show that the railroad continued miles into the forests south of Mono Mills.There were many other sources of human disturbance in the Mono Lake basin, such as local ranching to supply the miners, artificial duck ponds at Rush Creek, and much sheep grazing, so that no area in the basin can be described as "pristine." The type locality of Mentzelia monoensis J. M. Brokaw & L. Hufford, (J. M. Brokaw #367, 16 June 2007) is described as along California Highway 120 just north of Mono Mills. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

|

One of cutest little plant surprises is Eatonella nivea (D.C. Eaton) A. Gray, which is found occasionally in loose volcanic sand south of Mono Lake. It has a common name of White False Tickhead. I'm curious about how this plant got the name, and what a true Tickhead might be. Nevertheless, this little plant is about 3/4" high, but when the seeds mature, the peduncles (flower stems) elongate and raise the seeds above the plant into the breeze. Then at the end of the season, the few seeds left, the stems, and the leaves all collapse into a small hairy mass that gets quite sticky when wet, thus gluing some seeds, plant matter, and some of the volcanic sand into a little package to wait out the next spring. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

South TufaAlso along California Highway 120 on the south side of Mono Lake is the South Tufa trail. This is probably the most visited and most photographed places in the Mono Lake basin.This is a good place to see Sarcobatus vermiculatus (Hook.) Torr. or Greasewood. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

Locations: Mono Craters. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

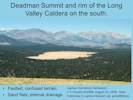

View west from Bald Mountain View west from Bald Mountain

|

Along the way, it skirts the north side of the Indiana Summit Research Natural Area, a large unnamed sand flat, and "Airfield Flat," to the top of an unnamed hill, before turning south to Deadman Summit. The terrain is highly faulted, and often confused with sand flats with internal drainage.

At Crestview, just south of Deadman Summit, is the type locality of Lupinus monoensis Eastwood (J. T. Howell, #14498, August 10, 1938, CAS272810). Alas, the name did not survive having been reduced in synonomy to Lupinus breweri A. Gray var. grandiflorus C. P. Sm., the Matted Lupine. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Little Sand FlatThe sand flats have a loose volcanic sand soil, little relief and usually internal drainage. A vegetation type could be defined for them, which would probably include: Ericameria parryi var. aspera, Hulsea vestita var. vestita, Phacelia bicolor var. bicolor, Phacelia hastata var. compacta, Astragalus monoensis, Lupinus duranii, Mimulus nanus var. mephiticus(?), Eriogonum spergulinum var. reddingianum, and Carex douglasii. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

Thinking about the kinds of vegetation found in the Mono Lake basin, most of them would fit well into vegetation types described in Saywer, et al.'s (2008) Manual of California Vegetation, 2nd edition. Perhaps, two additional types are needed. One would describe the volcanic sand flats found south of Mono Lake, and the other the stabilized sand dunes that are habitat for Tetradymia tetrameres (S. F. Blake) Strother, Four-part Horsebush. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Deadman Summit.

Mono Basin.

|

Deadman SummitDeadman Summit on US Highway 395, is the southwest corner of the Mono Lake basin.To the south, and in the Owens River drainage, is Crestview, really just a highway maintenance at the bottom of the grade to Deadman Summit. There are a number of collections made that give Crestview, Crestview Camp, or Crestview area, as the location. Perhaps Crestview was more of a settlement in past times. A few of the collections are far enough north of Crestview, e.g., 4.2 miles, that they are likely in the Mono Lake basin. To the north of Deadman Summit are Wilson Butte, a rhyolitic plug dome, and Hartley Springs, both in the Mono Lake basin. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The June Lake Loop and the four lakes of June Lake, Gull Lake, Silver Lake, and Grant Lake are all in my definition of the Mono Lake basin. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

Other articles:

Locations: June Lake. Snow Ponds. |

June Lake

There is a William M. Maule collection of Potentilla anserina ssp. anserina (JEPS44183) made at “Summit Lake.” In the survey made by S. A. Hanson in 1879 and 1883 for the U. S. Surveyor's office, June Lake was called Summit Lake. It was not called June Lake until the General Land Office map of field work done in 1929 (Bean, 1977). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Found in marshy areas near June Lake and Gull Lake is Gentianopsis holopetala (A. Gray) H. H. Iltis, the Sierra Fringed Gentian. This is one of two fringed gentians found in the Mono Lake basin. The other is G. simplex (A. Gray) H. H. Iltis, the One-Flower Fringed Gentian. It can be found along the edges of Dry Creek where it enters Big Sand Flat. Just outside the Mono Lake basin, G. simplex can also be found at Crooked Meadows. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

June Lake.

|

However, I have since found Crested Wheat Grass in three places: one among the Bitterbrush on the beach at the northeast end of June Lake, and two places in disturbed areas in the housing developments north of Gull Lake. So it is either fairly common in this area having been planted to reduce erosion, or is spreading into disturbed areas near the upper lakes. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Locations:

Reversed Peak.

|

Reversed PeakWest of June and Gull Lakes is Reversed Peak. This is the mountain made of resistent rock around which flowed the Horseshoe Canyon glacier. I include the entirety of Reversed Peak in the Mono Lake basin, even though its highest point, at 9455 ft (2881 m), is a thousand feet above my upper limit for the Mono Lake basin. This fact might be significant if there were actually any plant collections from Reversed Peak. However, to date, I have found none in California herbaria. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Snow Ponds.

|

On the south flank of Reversed Peak, west of June and Gull Lakes, is a relatively flat area roughly a square mile or so in size. Presumably this area was planed off by glaciers. There are a number of shallow ponds here, somewhere between five and eight, depending on how you count. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Locations:

Gull Lake.

|

Gull LakeGull Lake is just below June Lake. It is also a natural lake and the source of Reversed Creek, so called because it seems to run the wrong direction, west into the Sierra before joining Rush Creek to flow north through Grant Lake into Mono Lake. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Reversed Creek.

|

In August 2012, I took the Jepson Workshop in Tarweeds, presented by Drs. Baldwin and Strother. Since the tarweeds are mostly inhabitants of the California Floristic Region, it is not too suprising that there were none found in the Mono Lake basin. However, while walking in the Petersen Tract along Reversed Creek, between Gull Lake and Rush Creek, I came upon a small patch of Mountain Madia (Madia glomerata Hook.). This is an area that has long been disturbed by adjacent housing, and looked like it had been mowed earlier in the season. So it's possible that the Mountain Madia is a recent introduction. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reversed Creek joins with Rush Creek just above Silver Lake. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

|

Silver MeadowsThere are several large wet meadows, one of which has the local name of “Silver Meadows”.On the flanks of Reversed Peak just above Silver Meadows there are several glacier cut terraces. Arctostaphylos patula, the snowbush manzanita, makes its only Mono Lake basin appearance on one of these terraces just above the Silver Lake Tract. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Rush Creek.

Rush Creek (in Horseshoe Canyon).

Rush Creek delta.

|

Rush Creek

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

|

Silver Lake“Silver Lake” is the location of the only collection of Gentiana calycosa Griesb. -- Rainier Pleated Gentian -- in the Mono Lake basin (JEPS47074). The label on this collection appears to be written by hand by Willis L. Jepson. The UC/JEPS herbarium data base transcribed the collector's name as W. M. Manle, and I agreed. However, there were no other collections by a collector of that name. Dr. John Strother looked at the label with me and thought perhaps the handwritten “n” in Manle could be a “u”, making the surname “Maule.” It turns out there was a William M. Maule, who was Mono National Forest supervisor at the time this collection was made. It seems likely that Maule knew this was an unusual collection, and he knew where he was, when he sent this collection to Jepson at the University of California. So I have kept this collection in my checklist for the Mono Lake basin. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

|

In October, 2013, I searched the shores of Silver Lake, looking for Gentiana calycosa.

I didn’t find any.

I did find a very trampled shoreline, very much overused by fisherman, hikers, swimmers, and the like.

It would be amazing if an uncommon plant could survive in such a place.

So, for now, my suggestion is: William M. Maule did find Gentiana calycosa at Silver Lake in 1922, but it has been extirpated by overuse of the area.

In the meantime, I have had several conversations with hikers familiar with the area. They tell me there is something that sounds like a gentian along upper Rush Creek, where the trail crosses Rush Creek at a footbridge just below Agnew Lake. This would be in the Upper Mono Lake Basin, but perhaps a source of seed for the gentian around Silver Lake. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Locations: Silver Lake. |

Silver Lake | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Locations: Silver Lake (historical). |

Silver Lake (historical) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

View from outlet of Silver Lake to Carson Peak View from outlet of Silver Lake to Carson Peak

|

The outlet of Silver Lake at its north end. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Locations:

Grant Lake.

|

Grant LakeGrant Lake is in the transition from the Sierra Nevada to the Great Basin. There have been some unusual collections made around Grant Lake, unusual in the sense that they are the only collection of that taxon from the Mono Lake basin, by some well-known collectors, e.g., Milo Baker, Beecher Campton, and Mary DeDecker. So the Grant Lake area probably deserves some additional botanic work. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Horseshoe Canyon Moraine.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Parker Creek.

Parker Lake.

|

Parker LakeParker Lake, on Parker Creek, a tributary to Rush Creek, is just barely below the upper limit for the (lower) Mono Lake basin, and therefore every location immediately above Parker Lake is in the Upper Mono Lake basin.The Parker Lake trail is fairly easy, and a good place to see Leptosiphon ciliatus (Benth.) Jeps., or Whiskerbrush, in the middle portion of the trail. Watch also for Allophyllum gilioides (Benth.) A. D. Grant & V. E. Grant ssp. violaceum (A. Heller) A. G. Day, Dense False Gilyflower, which has been collected along this trail and in the vicinity of Lundy. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

|

Parker CreekAlong Parker Creek are a few wetlands, some perhaps artificially made by diverting water from the creek to water pastures.Along the edge of one of these wetlands, near the Los Angeles aqueduct intake, Poa compressa L. and P. pratensis L. grow in close proximity. This is also a good place to see the Geyer willow (Salix geyeriana Andersson) growing right by the roadside. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Bloody Canyon.

Mono Pass.

|

Mono PassThe historic route across the Sierra Nevada was across Mono Pass, descending Bloody Canyon, past Walker Lake.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Walker Lake.

|

Walker LakeWalker Lake on Walker Creek in Bloody Canyon is in the (lower) Mono Lake basin, and everything above Walker Lake is in the Upper Mono Lake basin. There are a few collections that give the location as “Bloody Canyon” without a further clarification about altitude, location relative to Walker Lake, etc. Generally, I treat those collections as being made in the Upper Mono Lake basin.Much of the land around Walker Lake is privately owned, and the road has a locked gate. To visit Walker Lake you must go to the trailhead atop the south lateral moraine, and then walk down 600 feet to the east or upstream end of the lake. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Locations: Walker Creek (Lower). |

Walker Creek | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pumice ValleyThe broad plain between the June Lake area and Mono Lake is called Pumice Valley. During major glacial periods this plain was covered by the Rush Creek glacier or high stands of Pleistocene Lake Mono. There are several ranches in the lower part of Pumice Valley. One of them was Cain Ranch, which is circled in the photo. The California Geological Survey made their Camp 120 near Cain Ranch. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This is a good place to review several of the early plant explorers in the Mono Lake basin. Among them would be William H. Brewer with the California Geological Survey in 1863, and then Victor Chesnut and Elmer Drew in 1889. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

California Geological SurveyThe Geologic Survey of California crossed the Mono Lake basin twice: once, with W. H. Brewer as the botanist, in early July, 1863, and again, with H. N. Bolander as botanist in early September, 1866. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| On the first visit, July 7-12, 1863, the California Geological Survey descended through Mono Pass on July 7th, which Brewer described as "the terrible trail" of Bloody Canyon. They established Camp 120 … "in the high grass and weeds by a stream a short distance south of Lake Mono," near the present day location of Cain Ranch. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Mono Craters.

|

On July 8th, Brewer and others visited Mono Craters, describing the scene as "…desolate enough -- barren volcanic mountains standing in a desert cannot form a cheering picture." There they made three collections that became types.

One of them (W. H. Brewer, #1823, July 8, 1863, UC32860, “UC” indicates the collection is in the University Herbarium of the University of California) was collected as Bahia lanata DC. Rydberg used this collection as the type of Eriophyllum monoense Rydb. However, that name did not survive as a succession of authors placed it in synonymy with various varieties of Eriophyllum lanatum (Pursh) J. Forbes (Syn: Bahia lanata DC.), ending with Eriophyllum lanatum (Pursh) J. Forbes var. integrifolium (Hook.) Smiley. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Locations:

Mono Craters.

|

They also collected the type of Hulsea vestita A. Gray in the “Very dry volcanic ashes near summit of volcanic mountains south of Mono Lake,” i.e., Mono Craters . | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

Locations:

Mono Craters.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

|

Not found by the California Geological Survey at Mono Craters is Frasera puberulenta Davidson (Inyo Elkweed). This is is not much of a surprise, though. The density of this plant is rather sparse, and it is generally found at the southern end of the Mono Craters, probably further south that the portion of the Mono Craters visited by Brewer and his companions. The type was collected by Carl A. Purpus in Cottonwood Creek Canyon of the White Mountains on August 1, 1896. It was originally named Swertia albomarginata (S. Watson) Kuntze var. purpusii Jeps. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

|

On July 9th, the survey traveled 10 miles north and established Camp 121 on northwest shore of Mono Lake. A collection was made here of Potentilla gracilis Hook. (W. H. Brewer, # 1826, July 9, 1863, UC12544) by Mono Lake, moist area. The Field Book name was Potentilla gracilis Dougl. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| On July 10th, they travelled to the islands with a man gathering eggs for sale in Aurora. They stayed overnight on Paoha Island in Mono Lake, returning to Camp 121, for the night of July 11, 1863. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| On July 12th, the survey departed Mono Lake for Aurora, Nevada | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| There are 26 collections with Brewer listed as the collector, and 17 collections with Bolander the collector. In addition, US has 13 collections from the same time period made at Mono Pass and Mono Lake with "State Survey" or "State Geological Survey" listed as the collecter. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

William H. Brewer was the botanist on the Geological Survey of California, 1860-1864. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

Henry N. Bolander (1831-1897) succeeded W. H. Brewer as the State Botanist of California and began making collections for the Survey. Bolander collected cryptogams and flowering plants, and became a specialist on grasses. He would continue this connection with the State Geological Survey until it was discontinued.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chesnut and Drew | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Victor King Chesnut was born on 28 June 1867 to John Andrew Chesnut and Henrietta Sarah King at Nevada City in the gold mining region of California shortly after the gold rush. The family moved to Oakland, California where he attended public schools. He was trained as a botanist and as a chemist at the University of California at Berkeley where he got a BS degree in 1890. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature Cited:

|

Elmer Reginald Drew (1865-1930) was a Californian by birth, and devoted the best years of his life to the cause of higher education in this state. After graduation from the University California in 1888 with a B.S. in Mechanics. Drew taught taught at the University of California until 1902 publishing his sophomore course in physical measurements in 1889, the same year he published "Notes on the botany of Humboldt County, California" in Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. This was an account of Chesnut and Drew's expedition to Humboldt County in July and August of 1888. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I assume that Chesnut and Drew were sent into the field by Edward Lee Greene. Greene became Instructor of Botany at the University of California in 1885, the first strictly botanical appointee. In 1890 the Department of Botany was established within the new College of Natural Sciences; the herbarium was initiated at the same time. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chesnut alone, and Chesnut and Drew together, collected for four years: 1887 - 1891. In 1887 they collected at Santa Rosa, Mt Tamalpais, and Mt Diablo. In July and part of August 1888, they traveled to Humboldt County, a trip about which Drew wrote. After their 1889 trip to Yosemite and Mono Lake, they collected in August 1890, around Lake Tahoe, and finally in April 1891 in Marin County especially Bolinas. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In 1889, Chesnut and Drew collected in Hetch Hetchy and Yosemite area, crossing over to Mono Lake. Starting June 16th and not arriving at Bloody Canyon until July 17th, they collected at Big Trees, Sugar Pine, Rosasco's, Columbia, Lake Eleanor, Cherry River, Hetch Hetchy, Eagle Peak, Yosemite Valley, Vernal Fall, Nevada Fall, Long Meadow and Cloud's Rest, Soda Springs and Mount Dana. On July 17th they ended at Bloody Canyon, perhaps camping near Mono Pass. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Locations:

Bloody Canyon.

Mono Basin.

|

From July 18th to the 21st, Chesnut and Drew collected in Bloody Canyon, the foot of Bloody Canyon, near Mono Lake, and at Mono Lake. Most of the collections give "Bloody Canyon" as the location. Therefore, I don't know whether the location would be in the Mono Lake basin, below 8400 ft, or the Upper Mono Lake basin. Generally, I have assumed the (lower) Mono Lake basin, unless the taxon is known to be found only at higher elevations. A few vouchers state "foot of Bloody Canyon," two state "Lake Mono," and one states "sandy plain near Lake Mono." Presumably, Chesnut and Drew visited the lake, and would have passed by Farrington's but there is no other evidence in the collections to support the presumption. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other articles:

|